19 Feb 202615 minute read

The Context Development Lifecycle: Optimizing Context for AI Coding Agents

19 Feb 202615 minute read

Why the next software development revolution isn't about code, it's about context.

We've spent decades perfecting how humans write code. We've built entire methodologies (waterfall, agile, DevOps, platform engineering) around the assumption that the bottleneck is getting working software from a developer's head into production. But that assumption just broke.

Coding agents are writing code now. Not just autocompleting lines, but writing features, fixing bugs, scaffolding entire services. The bottleneck has shifted. It's no longer about how fast we can write and ship code. It's about how well we can describe what the code should do, why it should do it, and how it should behave in the messy reality of our systems.

The bottleneck is context.

Experienced developers carry context around like muscle memory: the architectural decisions that shaped the system, the conventions the team agreed on, the business logic that only lives in someone's head from a meeting three months ago. A new team member struggles not because they can't code, but because they lack context. Now think about coding agents. Every session is a new hire. Every time an agent spins up, it starts from zero. No muscle memory, no hallway conversations, no institutional knowledge. It has only what you give it.

This means developers have inherited a new responsibility: translating implicit organisational knowledge into something structured enough for another entity to act on. Making the implicit explicit, at the right level of detail, for an audience that takes everything literally. And if context is the new bottleneck, then we need a development lifecycle built around it. I think what's emerging is a Context Development Lifecycle (CDLC), and it will reshape how we think about software development as profoundly as DevOps reshaped how we think about delivery and operations.

Let's be honest about where most teams are today. Context lives in .cursorrules files that someone wrote three months ago and nobody has touched since. It lives in CLAUDE.md files copy-pasted from a blog post. It lives in Slack threads where a senior engineer explains the authentication flow once and everyone is expected to have seen it. It lives in prompt snippets shared in a team wiki that may or may not reflect how the codebase actually works today.

There's no versioning. No testing. No way to know if context is still accurate. No way to distribute it when it improves. No way to detect when it conflicts with other context. And no way to tell whether it's actually helping or quietly making things worse. We treat context as simple documents to be copied around, not as artifacts to be developed over time.

This is where code was before version control. Before CI/CD. Before anyone thought to treat delivery as an engineering problem.

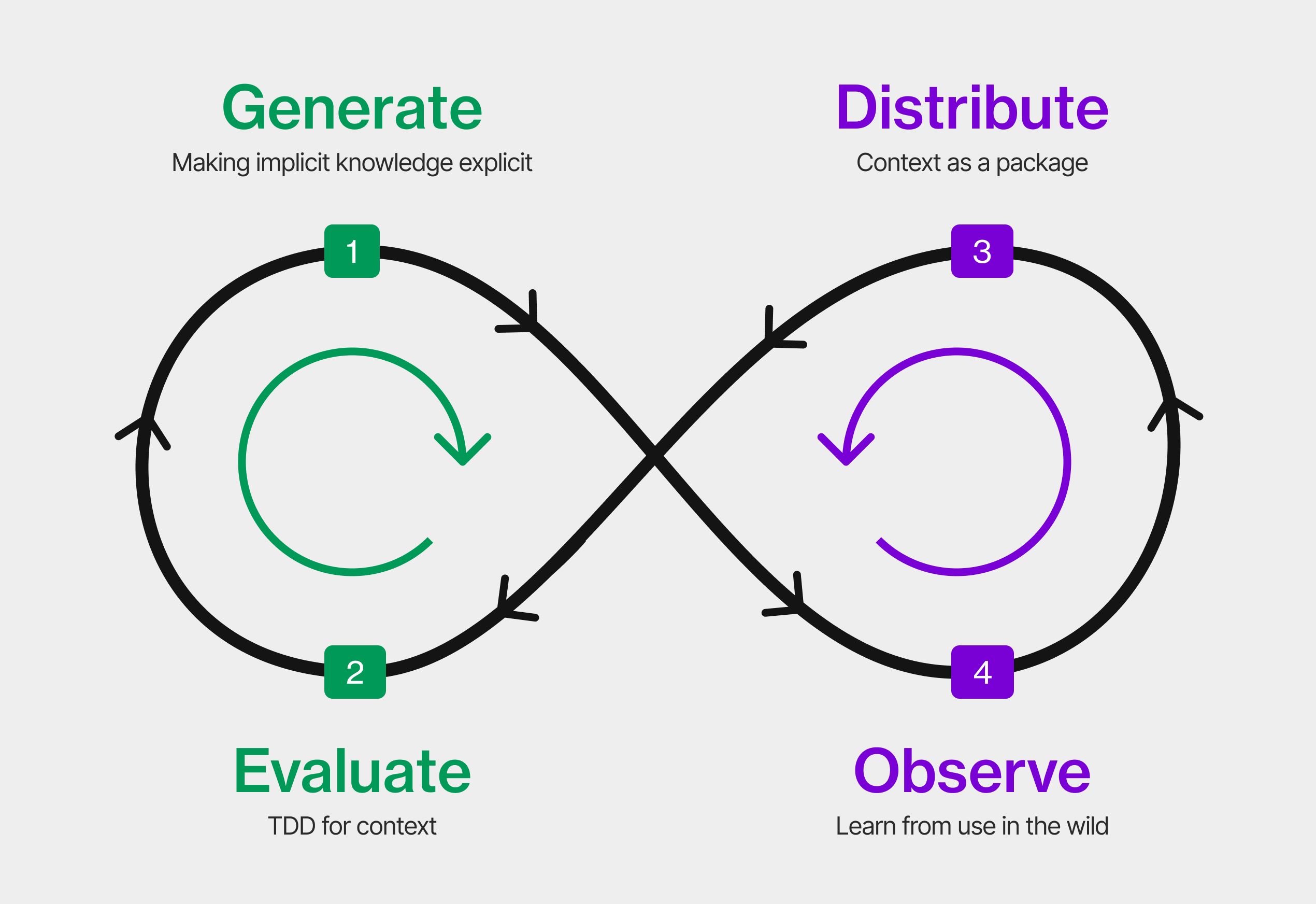

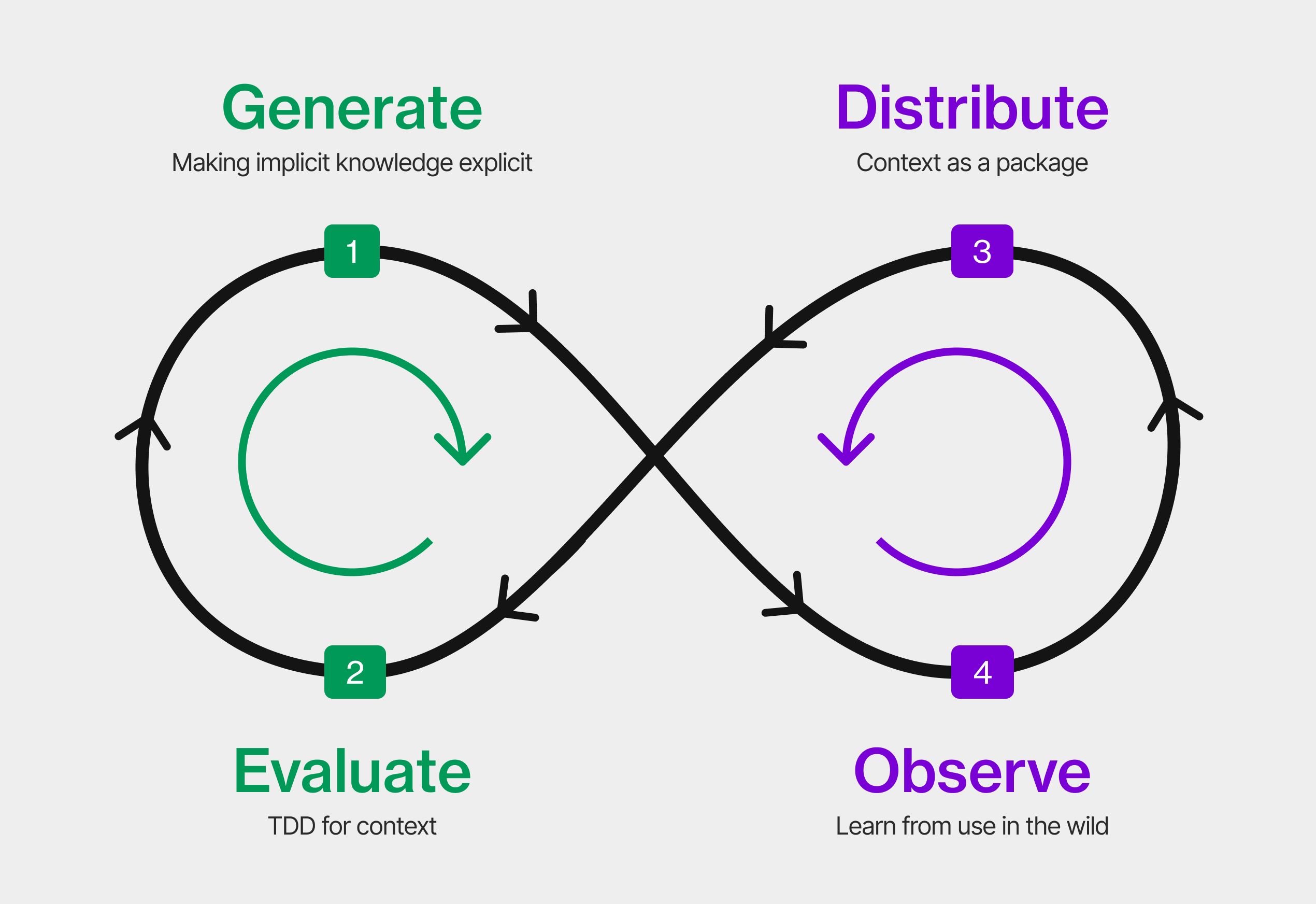

The four stages of the CDLC

If we treat context as an engineering artifact (something we generate, evaluate, distribute, and observe) a lifecycle emerges. The object moving through the pipeline isn't code. It's knowledge and intent.

Generate: making implicit knowledge explicit

Context authoring is specification work: capturing how a library should be used, what conventions a team follows, what constraints a system operates under, what patterns are preferred and which are forbidden. Whether you call them skills, instructions, rules, or specs, the work is the same. You can and should use AI to help author context, but you need to review and own what's created. The agent can draft, but the human decides what's true.

Context isn't just technical. There's technical context: coding standards, library usage, architectural patterns. There's project context: timelines, priorities, what's in scope and what's deferred. And there's business context: why the system exists, what the customer expects, what compliance requires. Agents need all three to make good decisions, and most teams only provide the first, if they provide any at all. And sometimes the model already knows something from its training data, so context should fill gaps in the model's knowledge, not duplicate it.

Context rots and conflicts. The best practice you encoded six months ago may be wrong today. The convention one team documented may contradict what another team wrote. When two pieces of context give opposing guidance, the agent doesn't raise a flag. It picks one, and you won't know which until the output surprises you. Managing context means managing its freshness and consistency, not just its existence. And when conflicts arise, you still need a decider: someone or some process with the authority to resolve which guidance wins.

Evaluate: TDD for context

You wouldn't ship code without tests. Why would you ship context without evaluations (evals, as the industry calls them)?

Testing context means defining scenarios and evaluating whether the agent's output matches your intent. Not just "does the code run," but "does it reflect the decisions, patterns, and constraints we specified." If this sounds like test-driven development, it should: write the expected behaviour first, run it, watch it fail, improve the context until it passes. Like testing code, there's a depth range. A single eval that checks your most important convention is better than none. Start wherever you are.

Evaluations turn context from a best-effort document into a verified, measurable artifact. LLMs are non-deterministic, so don't expect identical outputs. Think statistical quality control: "is the output still within spec." Evals also help you navigate model choices. What gain would you get from the new expensive model that just came out? Can you use the faster and cheaper one? Or the open one? Run your evals and you have an answer, not an opinion. Without them, every model change is a leap of faith.

When evaluations fail, it's tempting to blame the agent. More often, the failure is in the context. An ambiguous instruction. A missing constraint. An assumption that seemed obvious to a human but was invisible to the agent. Every evaluation failure is a specification you didn't write.

Distribute: context as a package

Context that lives in a single developer's project is useful. Context that flows across an organisation is transformative.

This is what makes distribution different from every previous "let's improve our documentation" initiative: developers actually want to do this. Writing context isn't a chore disconnected from their daily work. It directly improves the agents they rely on. Better context means less time correcting agent output, less time re-explaining conventions, less time debugging code that ignored a pattern they thought was obvious. For the first time, there's a selfish reason to share knowledge. The incentive is finally aligned with the work.

But without a registry, without versioning, without a way to push updates, context rots silently. That skill someone wrote six months ago, before a breaking change? It's actively teaching agents the wrong pattern, and nobody knows. Context also becomes an attack surface as it flows across teams, so it needs the same supply chain security posture you'd apply to any shared dependency. Treating context as a package (versioned, published, secured, and maintained) is the same insight that gave us npm and pip and cargo: knowledge scales when it has infrastructure.

Observe: learn from use in the wild

This is where the lifecycle becomes a loop.

It helps to equate this with how we already think about tests and observability in software. Our synthetic tests are never perfect. We do what we can, deploy the changes, and then observe production to spot failures and optimization opportunities. The same applies here. Evals catch what they can, but agents in the wild generate the real signal. They ask clarifying questions, revealing gaps. They make unexpected choices, revealing ambiguities. They produce code that works but doesn't match your intent, revealing unstated assumptions.

What did the agent know? What did it misunderstand? Where did it improvise because the context was silent?

We correct the context, add evals for what we missed, and redistribute. The loop continues. And agents themselves can help close it: the same agent that revealed the gap can draft an improved skill, suggest a clarification, or flag a conflict.

The parallel to DevOps

When DevOps emerged in 2009, we had development and operations as separate concerns. Code moved from one team to another with friction, delay, and blame. DevOps was a recognition that the lifecycle was one thing, not two. That building and running software were inseparable. That the feedback loop between them was where all the value lived.

But here's what people forget: DevOps was never really about tools or pipelines. It was about collaboration and communication. About developers and operations people building a shared vocabulary, learning to understand each other's constraints, and developing mutual trust through repeated interaction. The tools came later. The culture shift came first.

The CDLC has the same dynamic, but the collaboration is between humans and agents, and between teams that used to operate independently. Every conversation with an agent is a negotiation of understanding. You describe what you want. The agent interprets it. You see the result and realise your description was ambiguous. You refine. Over time, you develop shared terminology: terms that mean specific things in your codebase, patterns that have names, constraints that are understood without being restated every time.

The hardest part of DevOps was never the tooling. It was giving people the right incentives to work across boundaries. Developers and operations had different goals, different metrics, different reward structures. Getting them to collaborate required changing incentives, not just installing Jenkins. With context, the incentive problem is structurally different. Developers who write better context get better agent output. But the cross-boundary benefit happens too: every agent in every team that touches the same library or service benefits from that context, which means fewer bugs landing back on your desk. You don't have to care about the other team for them to benefit. The collaboration happens as a side effect of self-interest. That's a structural advantage that DevOps didn't have.

The CDLC is the recognition that creating context and operating with context are inseparable. That context needs the same engineering rigour we eventually gave to code: version control, testing, security, distribution, monitoring, and continuous improvement.

Infinite context windows won't save you

If context windows keep growing (and they are) does any of this still matter? The capacity constraint relaxes and the cost of including everything drops. But the lifecycle doesn't depend on scarcity. It depends on quality. An infinite window doesn't write your context for you, and it actually makes conflicts worse: more context loaded means more contradictions to navigate. The challenge shifts from "what to include" to "how to keep it consistent, current, and trustworthy." From curation to governance. That might be harder, not easier.

The question for your team

You've invested in getting agents to write code. What have you invested in giving them the context to write it well?

Do you test your context? And when you switch models, do your evaluations still pass?

The teams that win in the agent era won't be the ones with the best models. They'll be the ones with the best context: generated, evaluated, distributed, and continuously improved.

That's the Context Development Lifecycle. And in the next piece, I'll make the case for why running this cycle over time produces something even more valuable: a compounding knowledge advantage that your competitors can't copy.